By Michael Konieczny

Cross posted at the Perseus Updates blog.

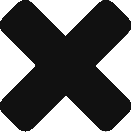

Visitors to the Open Greek and Latin digital library often ask us about what appear to be fragments of “code” alongside the list of authors in the library’s collection:

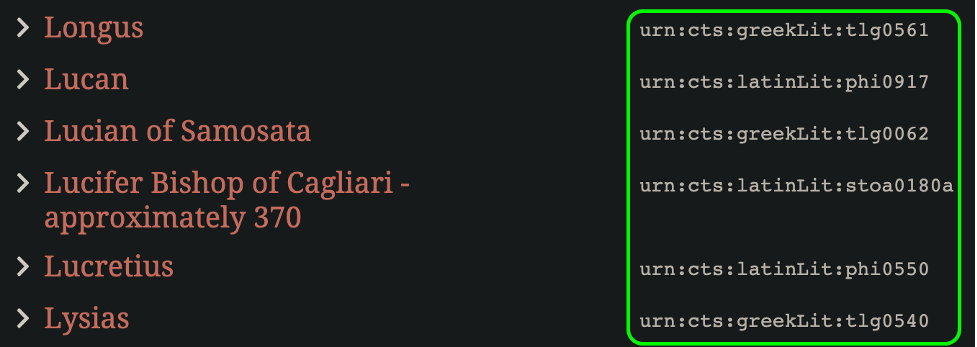

If you expand the list of works by a given author, you’ll notice that a similar line of “code” appears next to the title of each work, but with an extra element added at the end:

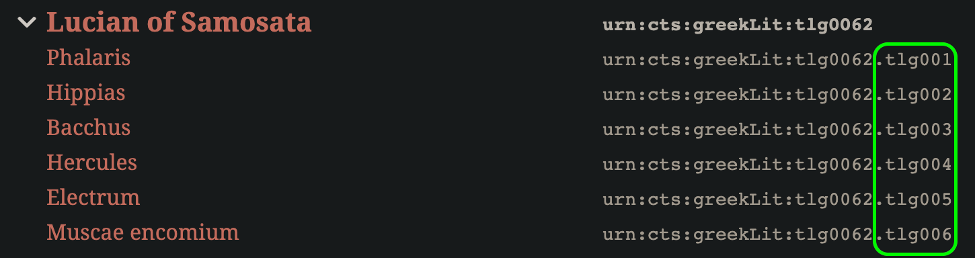

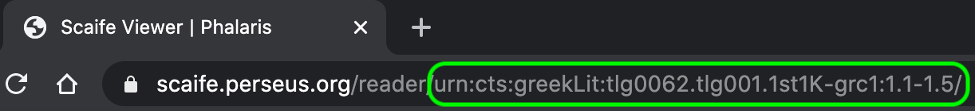

And once you actually go to read a work, you’ll notice an even longer sequence of characters in the right sidebar, and an identical one in your browser’s address window:

These character sequences are called CTS URNs (Canonical Text Services Universal Resource Names), and they are an essential component of the Open Greek and Latin infrastructure. Simply put, CTS URNs are unique identifiers that make it possible to retrieve a specific passage of text from a database. In this blog post we’ll take a closer look at how CTS URNs work, and why they are so important to building the digital Classics library of the future.

Needle in a Digital Haystack: Universal Resource Names

Suppose you pay a visit to your local library to check out a copy of your favourite Jane Austen novel. If your library is very small—say, 200 items or less—you will probably be able to locate the book quite easily just by scanning your eyes over the shelf. But this method would quickly become impractical in a library with thousands or, in some cases, millions of items in its collection.

In order to simplify the search and retrieval process, libraries assign each book a unique call number, and then use the call numbers to arrange books in a logical order across floors and shelves. Armed with a call number and a floorplan of the library, you can easily find a specific book from among millions of others—assuming no one has misplaced or stolen it!

Call numbers are an example of metadata: information about an object, such as its location, size, or creation date, that is separate from the object’s contents. Metadata is important for keeping track of items in a collection and understanding how they relate to one another. Good metadata also makes it possible to perform statistical analyses that can yield insights into the collection as a whole.

In many ways, Universal Resource Names, or URNs, are analogous to the call numbers in a library. Each item in a digital collection is assigned a unique URN that distinguishes it from every other item. When you log on to the collection, your computer downloads an inventory containing the URN of every available text—this is what you see when you browse the OGL library. The inventory is updated whenever a new text is added to the database, so that you never end up with “dead” links or an incomplete catalog.

When you select a text you want to read, your computer sends the URN of that text to the OGL server, which responds by sending back a copy of the text in the form of an XML document (on which more in a future post).

Finding Your Way: Canonical Text Services

In theory, a URN could be any random sequence of characters, as long as no two URNs are the same. This kind of system would tell you what texts are available to read, but nothing about the way in which the collection is organized or how different texts relate to one another. In particular, it would be difficult to group together different texts by the same author, an essential feature of both physical and digital libraries.

To solve this problem, projects such as OGL use a system known as Canonical Text Services. Despite the name, CTS has nothing to do with labeling texts as either “canonical” or “non-canonical”. Rather, CTS provides a set of rules for generating URNs that reflects the logical organization of texts into groups and subgroups.

If you examine the list of works by Lucian of Samosata in the screenshot above, you will notice that each URN begins with the same sequence of characters: urn:cts:greekLit:tlg0062:. The letters urn:cts: appear in every URN, and indicate that we are employing the CTS citation format. greekLit locates the text within one of OGL’s main subcollections, Greek Literature (other subcollections include Latin Literature,latinLit, and Hebrew Literature, hebLit). Finally, tlg0062 is the sequence that has been assigned to the author Lucian. In fact, urn:cts:greekLit:tlg0062: is a complete URN on its own: it distinguishes the author Lucian of Samosata from all other authors in the OGL library. Individual works are identified by appending a suffix to the URN of the author: tlg001, tlg002, and so forth. This way, all works by Lucian appear together as a single text group.

This sort of system, in which smaller categories are nested within larger ones, is an example of a hierarchy. In addition to grouping together works by the same author, the hierarchical format of CTS URNs makes it possible to identify a specific passage within a text in a way that mirrors the text’s internal structure.

Navigating the Text

Classicists will be familiar with the system of citing passages of text by canonical reference. Depending on their genre and length, most ancient works are divided into segments such as books, chapters, or, in the case of poetry, line numbers. Longer segments, such as books, are themselves usually divided into shorter ones, so that the result once again is a nested hierarchy. For example, the citation “Thuc. 5.84.1” refers to book 5, chapter 84, section 1 of Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War, which happens to be the opening scene of the famous Melian Dialogue. Longer passages can be identified by using a range: to cite the Melian Dialogue as a whole, we can write “Thuc. 5.84-116,” that is, Thucydides book 5, chapters 84 to 116.

The advantage of canonical references is that, unlike page numbers, they remain valid no matter what edition of a work is being used. They are also more suitable for citing texts in a digital environment, where the concept of physical page numbers is no longer very meaningful.

To identify a specific passage of text within the CTS framework, the URN of the text can be extended in a way that resembles the canonical references above. Here is the URN for book 5, chapter 84, section 1 of Thucydides: urn:cts:greekLit:tlg0003.tlg001.perseus-grc2:5.84.1. In this example, the sequence perseus-grc2 identifies a particular version of the text stored in the OGL database, while 5.84.1 points to the specific passage. A longer passage can likewise be expressed as a range: urn:cts:greekLit:tlg0003.tlg001.perseus-grc2:5.84-5.116. Note that the same hierarchical levels must be included on either side of the range: 5.84-5.116, not 5.84-116, which would prompt an error message.

When you access a text on the OGL library, your computer is provided with information about the text’s citation structure. As you navigate through the text, your computer sends a URN of the target passage to the OGL server, which returns a copy of the passage, again in the form of an XML document. While you can progress forwards and backwards through the text sequentially, you can also enter a specific URN into your browser’s address window: assuming the URN is formatted correctly, this will take you directly to whatever passage you are interested in.

Planning for the Future

We have seen that CTS URNs provide a logical way of retrieving texts and passages of texts that reflects the organization of a collection and the internal structure of the texts themselves. But perhaps the question remains: Why is such a system important in the first place?

While a simple reading environment is possible without URNs, the CTS framework allows us to unlock the full potential of a digital edition. By assigning a unique identifier to every passage of every text, CTS URNs make possible large-scale textual analysis that in the past would have required hundreds of hours of manual tabulation. With the proper software, we can easily find out how word frequencies, metrical patterns, and even syntactical structures vary within and across texts. The discovery of statistically-significant variations might help resolve disputes over the authorship of a text, for example, or to precisely quantify the way in which an author’s style developed over the course of their career.

In addition to this, the CTS framework helps protect a digital repository from becoming obsolete in the face of changing technology. Since URNs are just strings of characters, they will remain valid no matter how the technology for processing and displaying texts evolves in the future. By investing in this system, the Open Greek and Latin Project is positioning itself to take advantage of exciting innovations in the field of digital humanities, and to serve as an invaluable resource to Classicists for generations to come.